Privacy Myth 3: No Expectation of Privacy in Public

The question of whether we can expect any privacy when we are out in public is often raised to justify mass surveillance. From a legal perspective, courts have settled this issue numerous times, going back to 1967. There can be at least some expectation of privacy in public, depending on circumstances. This was summarized most famously in a landmark privacy court case called Katz, by Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart.

"The Fourth Amendment protects people, not places."

Yet this myth persists, largely thanks to how complex the concept of privacy is, and also thanks to our innate desire to reduce complex issues to simple, absolute statements. If we were to aim for a more accurate reduction, the result might be: Our expectations of privacy ought to be different when we're in public than when we are in private.

This reduction is not as satisfying as the myth it attempts to replace, but it provides for consideration of nuanced contexts that arise as society evolves. These new contexts are getting more tricky everyday. Let's consider a modern example that explores the complexity of privacy while in public.

Considering Mass Surveillance

It is apparent to everyone that when we stand in a place populated by members of the public, the fact of our presence in that place is publicly exposed. For example, people who stand across the street from me can see my face and know: there is Seth, at that place and time.

Newcomers to privacy conversations often stop here and conclude that all activity in public is therefore naturally unrestrained by privacy norms or laws. However, our current era of information technology adds a lot of problems to that conclusion.

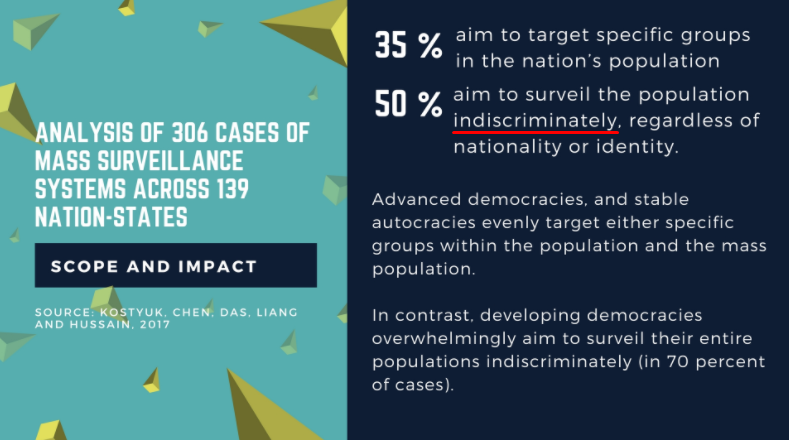

Whereas observing someone on the street once required a human to be present to perform the observing, those days are long passed. It is now possible (and increasingly likely) that our presence in a public place can be observed by hidden machines, not only at a targeted time (as an investigator may do), but rather at all times and in all places.

In a world of 24/7 data tracking, warehousing, and mining, technology has transformed obscurity, accessibility, and transparency of personal information in ways that subvert the utility of the “reasonable expectation of privacy” constitutional standard.

Such round-the-clock observation of an individual has historically only been accomplished with great effort to the observers, and at a high cost which naturally limited how many of us could be targeted by such persistent observation at one time. In fact, to address the question of whether an invasion of privacy has taken place, courts have relied on the question of how much effort and costs were expended to gather the information.

But the great cost and effort, too, are limitations of the past.

The ubiquity of the internet means technology is easy to deploy that will observe millions of people at the same time, removing historic limitations on who can be observed, for how long, and for what purpose. Technology has enabled permanent, mass collection of such data, for any purpose (or no purpose) whatsoever.

Going beyond mass observation, we now have the ability to commit that collected information to an infinitely-growing record. That record can be permanent, such that all of our public activity can be converted to persistent records, accessible to anyone able to reach it, without expiration.

What, then, happens to such automatic, indiscriminate, permanently-stored, infinitely-growing records of each person's activities? It is left to our imaginations. Both the public and private sectors have many uses the average person can hardly imagine. The data could be searched, sold, converted, reproduced, mined, correlated or otherwise manipulated by algorithmic means to produce a result that we, members of the public, never imagined, intended, or agreed to. Our new era of "deep fakes" and drone surveillance are two such examples.

Are you implicitly agreeing to participate in such programs, by merely setting foot outside your door?

The paradigm of "privacy in public" referring to my individual privacy being impossible, thanks to your individual observation, is gone. The question of privacy in public has evolved to a new question: Do hidden mechanized observers have the right to indiscriminately create unregulated, permanent records of every person's every action?

We believe that no such right to domestically collect information via dragnet exists. Rather, we believe the U.S. Constitution and California's constitution guarantee us the right to protect our information, including the storage, access, dissemination, and processing of our data into derivations or new products based on our information.

As such, we believe that each individual is a stakeholder in protecting their information, including the information collected about them while they are acting in shared or public spaces.